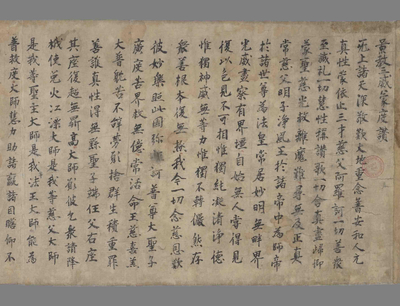

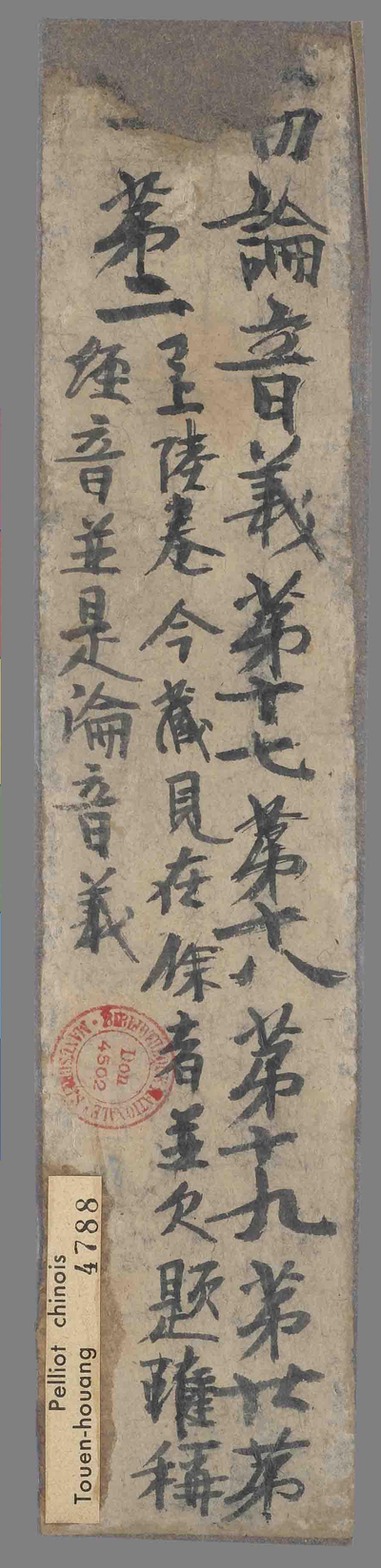

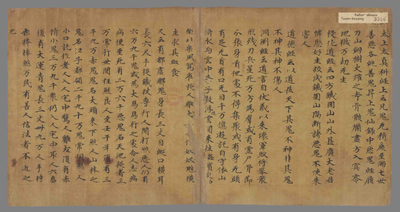

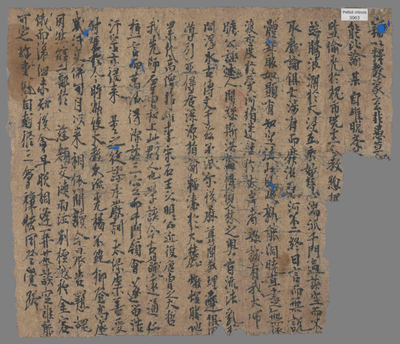

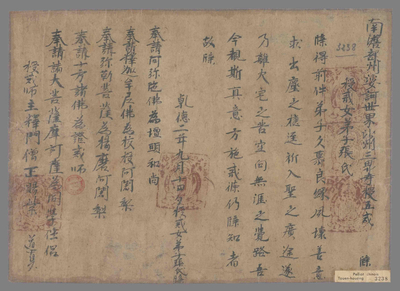

大乘百法明门论开宗义决

-正

名称

大乘百法明门论开宗义决

编号

P.2077

年代

待更新

材质

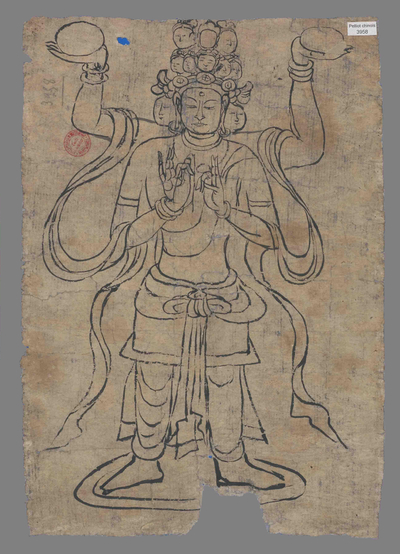

墨繪紙本

语言

中文

现收藏地

法国国家图书馆

尺寸

简述

待更新

有疑问?找AI助手!

AI小助手

稍等片刻,AI正在解锁知识宝藏

稍等片刻,AI正在解锁知识宝藏

正在分析经卷中,请稍作等待…

扫码分享

打开微信,扫一扫

打开微信,扫一扫

*以下文本内容由DeepSeek与腾讯混元生成,仅供参考。

*以下文本内容由DeepSeek与腾讯混元生成,仅供参考。